A Perfect Pairing: FME and RapidEye Imagery in La Rioja, Spain

In the world of wine, La Rioja is a name with a long-standing tradition behind it. This province in northern Spain is home to around 40,000 hectares of vineyards devoted to producing wines with the Denominación de Origen Calificada Rioja designation – and they produce 250 million liters of it every year. So it’s not surprising that the GIS and Cartography department at the Government of La Rioja has much of their efforts directed at vineyard management.

La Rioja’s resident Certified FME Professional Ana García de Vicuña is no newcomer to the world of wine herself – she has spent much of the last decade applying remote sensing, GIS and GPS technologies to various aspects of viticulture. We had the opportunity to see some of her rather impressive work recently, and if you were at an FME World Tour 2013 event this year, you may have seen it profiled.

Ana approached a recent vegetation index calculation project with an interesting twist – using FME to do the entire analysis, as the algorithms she needed weren’t available in her remote sensing software.

Starting with 22-meter RapidEye multispectral images, her task was to calculate three different indexes, which would be used to classify agricultural land cover and crop conditions:

- NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index)

- TCARI (Transformed Chlorophyll Absorption in Reflectance Index)

- OSAVI (Optimized Soil Adjusted Vegetation Index)

Ana needed to use the visible red and green spectral bands, plus near-infrared. This data is stored as a “digital number”—DN—with a range between 0 and 255. To calculate a vegetation index, the DNs need to be converted to “top of atmosphere”—ToA—reflectance values. This is a two-step process. First, the DNs are converted to radiance, and second, the radiance is converted to ToA reflectance. These are then used to produce the vegetation indexes.

Let’s walk through her solution.

Step 1 – Find Values

Each pixel’s DN is converted to a radiance value by multiplying it by the radiometric scale factor, producing a per-pixel value in watts per steradian per square meter.

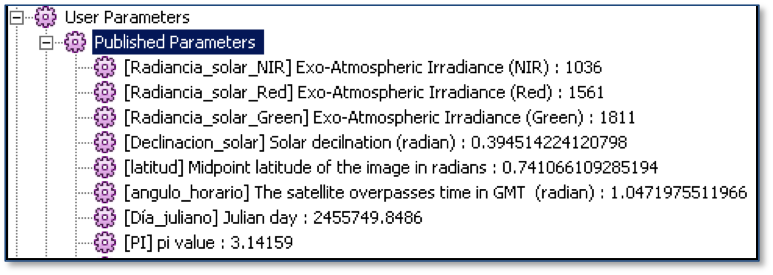

That radiance value is then used to calculate ToA reflectance, using a number of variables including the sun’s distance from the earth and the geometry of the incoming solar radiation. The variables, different for each scene, are defined as parameters in the workspace.

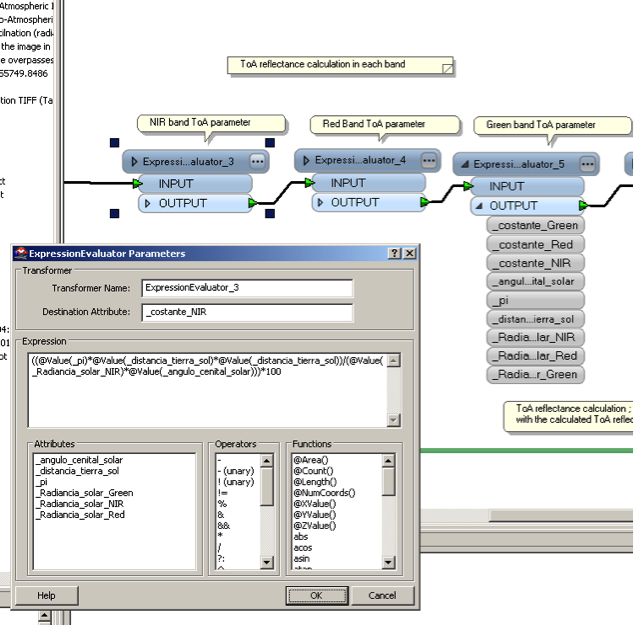

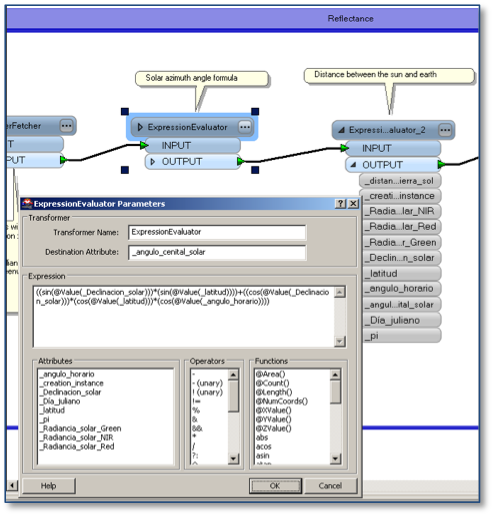

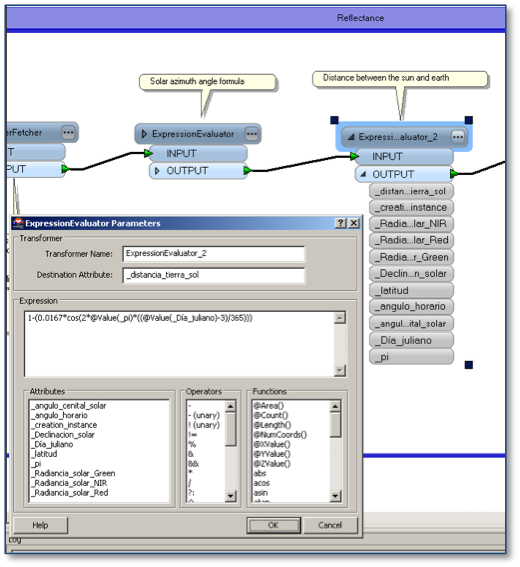

A ParameterFetcher is used to retrieve the values, and the solar azimuth angle and distance from the sun are calculated.

And finally, ToA reflectance parameters are calculated for each band.

Step 2 – Calculate Vegetation Indexes

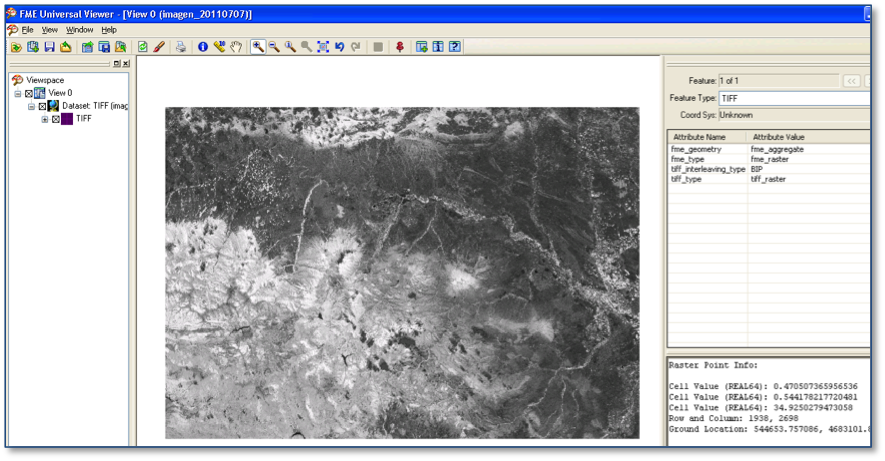

Next, each band – red, green, and near-infrared – is multiplied by its calculated ToA reflectance parameter, and the resulting bands are separated. Each vegetation index is generated, and the results are written out to TIFF – a ToA reflectance image for each band, and the NDVI, TCARI, and OSAVI values, stored within the raster output.

Further Thoughts

Though this process was designed specifically for the RapidEye imagery selected for this particular project, Ana tells us that the workflow would be simple to adapt to other imagery sources, index types, and algorithms – and she would definitely consider doing so over using purpose-built software. Why? Automation and control.

“FME is very logical to me,” says Ana, “and it is so easy to implement through all of your processes because of this. I use it every day in my work – it’s simple to see how a workspace is functioning, and also to see the potential power and what you can do. If I can work in FME, I will.”

Ana’s work certainly caught the attention of many of our World Tour attendees who are now looking at new ways to approach rasters in FME. You can learn more about it on our website, or head over to FMEpedia for detailed answers to your raster questions.

Here’s to innovation with FME – ¡Salud!